Written by Dr. Shannon Dea

On Sept. 8, in the midst of all of the global reaction to Queen Elizabeth’s death, Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) issued a shocking and worrisome statement distancing itself from Uju Anya, a professor in its department of modern languages.

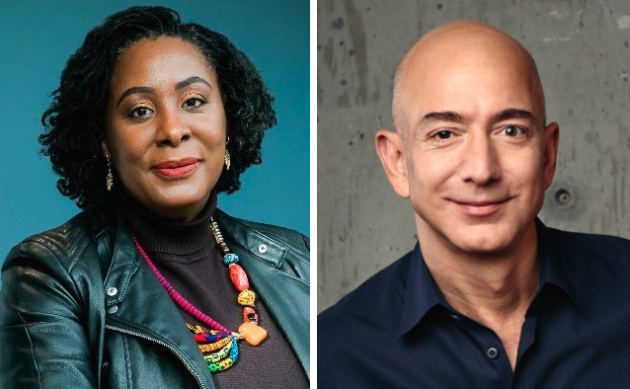

As word spread that the Queen was dying, Dr. Anya, a Nigerian-born professor of applied linguistics, critical sociolinguistics, and critical discourse studies had tweeted, “I heard the chief monarch of a thieving raping genocidal empire is finally dying. May her pain be excruciating.” Unsurprisingly, the tweet received some very disapproving responses. But it wasn’t until about four hours later when Amazon owner Jeff Bezos weighed in that the tweet went super viral.

Mr. Bezos, who has 5.1 million Twitter followers, retweeted Dr. Anya’s original post with the comment “This is someone supposedly working to make the world better? I don’t think so. Wow.”

With Mr. Bezos’s tweet, the backlash against Dr. Anya intensified exponentially. Dr. Anya reports that she received 500 emails within minutes of Mr. Bezos’s tweet, many of them using a racist slur to refer to her. She dug her heels in, tweeting “If anyone expects me to express anything but disdain for the monarch who supervised a government that sponsored the genocide that massacred and displaced half my family and the consequences of which those alive today are still trying to overcome, you can keep wishing upon a star.”

Twitter deleted the earlier tweet for violating its rule against abuse or harassment, which reads “You may not engage in the targeted harassment of someone, or incite other people to do so. This includes wishing or hoping that someone experiences physical harm.”

Then came Carnegie Mellon’s tweeted statement: “We do not condone the offensive and objectionable messages posted by Uju Anya today on her personal social media account. Free expression is core to the mission of higher education, however, the views she shared absolutely do not represent the values of the institution, nor the standards of discourse we seek to foster.”

Despite Carnegie Mellon’s obligatory sop to free expression, the statement three times undermines academic freedom. First, it characterizes Dr. Anya’s posts as “offensive and objectionable.” Second, it says Dr. Anya’s comments don’t represent the values of the institution. Finally, it implies that Dr. Anya’s tweets do not meet Carnegie Mellon’s standards of discourse. Let’s work through each of these in turn.

The first of Carnegie Mellon’s undermining statements criticizes the content of Dr. Anya’s views as “offensive and objectionable.” Let’s be clear: some of the work professors do is offensive and objectionable. It is the job of universities to expand the horizon of our understanding, including through extramural expression on matters of public concern. When we push outside of current orthodoxies, it can cause offense and objection. Further, some scholars aim to cause offense and objection. Dr. Anya certainly did. Her tweet was calculated to produce just such a response. She is a critical race scholar who was engaging in public commentary on violent colonial harms. She chose to express herself strongly – offensively even – to better convey the force of her disapproval. But it is precisely controversial work – including the offensive and objectionable – that requires the most robust academic freedom protection. No one is trying to silence inoffensive scholars!

Next, Carnegie Mellon says that Dr. Anya’s views don’t represent the values of the institution. What a remarkable and unnecessary statement! No one could possibly think that Dr. Anya is speaking on behalf of the university. And indeed, her Twitter bio says “views are mine.” While it can provide helpful clarity for scholars to include such notes on their social media accounts, it is not strictly necessary. Universities are constituted by scholars with a wide range of perspectives, values and methods – some of these inconsistent with others. That is a feature, not a bug. The university can’t share all of those different values and no one expects it to. However, all of those different approaches ought to be united under the university’s higher value of scholarly pluralism. In disavowing Dr. Anya’s position, Carnegie Mellon weakens that commitment. Instead of pluralism, it’s pluralism except for this.

Finally, the Carnegie Mellon statement deplores Dr. Anya’s standard of discourse. Again, universities must adopt the broadest conception of the standards of discourse. In their communications, university scholars should not break the law or engage in disinformation. Dr. Anya did neither of these things. She shared a strong, sincere opinion about a public figure. She did so in a way that was shocking, but universities cannot and should not require their members to be polite. Indeed, on matters of grave moral concern such as the colonial harms of the British monarchy, politeness might be the wrong standard of discourse.

In combination, Carnegie Mellon’s three disavowals of Dr. Anya’s tweets risk creating a chilling effect for other scholars – and this in the context of a Black woman professor who was being berated by one of the world’s wealthiest men, the Twitter followers he sicced on her, and the media who took up the story. When an academic staff member receives that kind of acute censure from the public, it is all the more important that their university have their back. Carnegie Mellon should have reached out to Dr. Anya to check in on her and offer support. If it issued any statement at all, it should have been a statement defending Dr. Anya’s right to vigorous critique.

The university’s undercutting of Dr. Anya’s academic freedom is especially shocking given the careful work that it has been doing on academic freedom. In 2020, in response to a controversy over a policy school appointment, Carnegie Mellon president Farnam Jahanian struck a Commission on Academic Freedom and Freedom of Expression and issued an impressively nuanced, well-informed defense of academic freedom. Here is an excerpt:

Academic freedom… protects the critical exchange of ideas that has sparked scientific innovation and important conversations about equity and justice, and has launched new areas of inquiry unbounded by the socio-political context of the day. At the same time, freedom of expression, a cornerstone of our democracy that is protected by the First Amendment, guarantees our right to speak our mind about matters of public concern in language appropriate for achieving our purpose.

The statement goes on to discuss the difficulty and complexity of balancing robust academic and expressive freedom against the need to promote “an inclusive, civil and nurturing environment for all.” It continues:

As we facilitate important debate on critical issues, we recognize that in rare cases, such discourse may be offensive or alienating to individuals or groups on campus, even as those individuals or groups have the same freedom to refute those ideas to which they object, or which are contrary to our community’s values. This tension is exacerbated in the current American socio-political climate, and all the more so by the accelerated and pervasive impact of technology and social media.

It is immediately obvious that Dr. Jahanian’s statement and Carnegie Mellon’s Sept. 8 tweet were not written by the same person or even by the same department. Dr. Jahanian’s statement is deeply cognizant of the importance of academic freedom, of the complexities of defending it, and of the new challenges posed by social media. By contrast, the tweet betrays no awareness of any of those things. It is pure, panicky damage control and deeply at odds with the work of Dr. Jahanian’s commission.

So, what exactly put the university into damage control mode? Well, they are no doubt receiving tons of phone calls, emails and social media messages complaining about Dr. Anya, demanding her termination and withdrawing donations. That is always a tough storm for a university to weather, but in the age of social media firestorms, universities need to have good playbooks ready for such flare-ups.

It is also quite possible that they were frightened of losing the support of one of their large donors. In December 2020, Amazon donated $2 million to the university. The tweet from Mr. Bezos may well have raised alarm bells in the donor relations department even if Amazon did not contact the university directly. Honestly, though, I would be shocked if Mr. Bezos is even aware of the donation. Amazon is worth $1.36 trillion and Mr. Bezos’s personal worth is $151 billion. He was the first centi-billionaire in history. He sheds $2 million like most people shed dead skin cells. Thus, he probably wasn’t trying to intimidate the institution. Nonetheless, one can imagine the donor relations team feeling pretty anxious when they saw Mr. Bezos’s tweet. I’ve written before about how important it is for universities to have good policies and training to ensure that the development side and the academic side understand each other’s roles and maintain good, healthy boundaries.

In the nearly two weeks since Carnegie Mellon issued its statement, thousands of students and fellow scholars have signed an open letter in solidarity with Dr. Anya. The professor thanked her supporters and reassured them that the university has no intention of firing her.

Is it too late for Carnegie Mellon to do the right thing? Since Sept. 8, they have been silent about the case on both social and traditional media. Perhaps they are waiting out the storm. No doubt they are also having internal conversations about how the matter played out. In the end, if Carnegie Mellon wishes to land in the right place, it must issue a retraction, an apology to Dr. Anya, and a declaration of vigorous support for her academic freedom. To allow its hasty Sept. 8 statement to stand undermines the work of the Commission on Academic Freedom and Freedom of Expression, betrays a Black woman scholar, and sacrifices the scholarly mission of the university to public opinion.

Leave a Reply