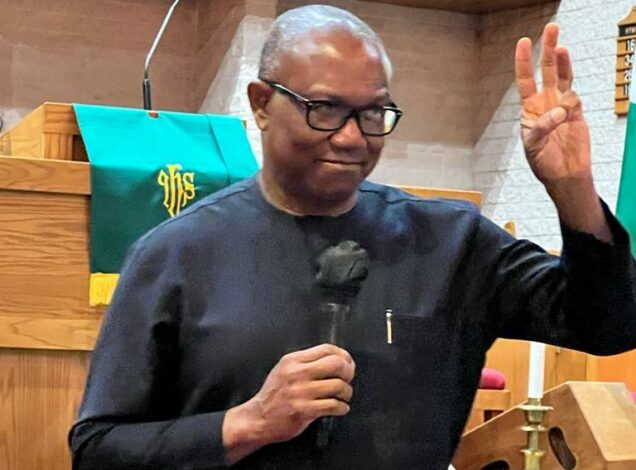

Sonala Olumhense, the distinguished journalist, attended an event in New York last week where Peter Obi, the Labour Party presidential candidate, gave a speech. According to Olumhense, the presidential candidate was brilliant, articulate, and on top of the key economic and political problems afflicting Nigeria. Even more important, the Nigerians living in the United States who attended the talk came from diverse ethnic backgrounds, illustrating the fact that the Obi phenomenon currently sweeping across the country is pan-national and not restricted to the Igbo as some mischievous critics of the candidate would have Nigerians believe.

Another observation which Sonala Olumhense made that I found significant was that the ongoing debate on Peter Obi’s candidacy is about Nigerians truly debating among themselves the present state of the country and what steps to take to turn things around. It is a frank admission that Nigeria under President Muhammadu Buhari is in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) of the hospital; that the All Progressives Congress (APC) has misgoverned the country these past seven years; and that the APC’s presidential candidate, Bola Tinubu, who played a key role in foisting President Buhari on Nigerians in 2015, must take ownership of the Buhari disaster.

This short essay is a contribution to this debate; an examination of Peter Obi’s policy platform to the extent that it bears on the Nigerian poor. The Labour Party presidential candidate has himself said that he will anchor his campaign on the estimated 100 million Nigerians presently living below the poverty line. He has also committed himself to rolling out policies and programmes designed to slay the monster of poverty in the country. Young Nigerians are the powerhouse of the Peter Obi movement. The overwhelming majority of these young people are either poor or unemployed or both. There is therefore a sense in which it can be said that they too are included in Peter Obi’s promise to confront poverty frontally.

Another point to be noted is that Peter Obi is running for president on the platform of the Labour Party, an organization founded by the Nigerian Labour Congress in 1989. It is an open secret that the Labour Party has not been faithful to its working class origins these past 33 years. In fact it has repeatedly served as a ready platform for buccaneer politicians who use it to access power and as quickly abandon it. The party has however, been given a new lease of life of recent. Ayuba Waba, the Nigerian Labour Congress President, is leading efforts to re-position the party as a true and robust vehicle of Nigerian workers for the 2023 general election. Ayuba has declared that the NLC, working within the Labour Party, will campaign for Peter Obi because they see him as the instrument through which suffering workers in the country will be salvaged.

At a retreat organized by the Labour Party in Abuja last week to which the noted human rights lawyer Femi Falana was invited to speak, a case was made for a campaign strategy for Peter Obi that will be truly innovative and make a sharp departure from the cynical practices of the All Progressives Congress and Peoples Democratic Party that usually rely on stolen money, intimidation and open violence to muscle their way to power. The Peter Obi campaign, Femi Falana insisted, should be anchored on the true yearnings of the Nigerian poor as enunciated by the programme spelt out in the Nigerian Workers Charter of Demands.

Peter Obi is yet to unfurl his manifesto but I argue that this manifesto must be informed by the contents of the Nigerian Workers Charter Of Demands. I am not saying that he should adopt the charter wholesale, but effort must be made to at least meet the document half-way. Such programmes as Universal Health Coverage modeled on Great Britain’s National Health Service wherein health care is free at the point of use, free education at primary and secondary school level supported with generous subsidies in higher education, and a vigorous policy of subsidized housing for the poor, must constitute the cornerstone of Peter Obi’s manifesto.

In his public speeches so far, Peter Obi has tended to give more attention to getting Nigerians to be productive again, pointing out that the usual practice of consumption without production has been the bane of the Nigerian economy since independence in 1960 and that the time has come to get out of this rut. I agree with Obi’s position. It is important that steps be taken to revive the Nigerian economy as this will benefit the poor as well as everyone else. But I also argue that specific pro-poor policies should be adopted by a future Peter Obi government for the simple reason that since 1960 successive governments in this country have treated the poor as irrelevant and powerless citizens whose needs are routinely ignored without consequence.

It makes political sense to anchor a presidential candidate’s campaign on the poor in today’s Nigeria. The poor are in the majority, and when you sufficiently demonstrate that their welfare is uppermost in your mind, they usually reward you with their votes and loyalty. Malam Aminu Kano in his lifetime demonstrated this truth. In the 1950s and 1960s Aminu Kano’s Northern Elements Progressive Union (NEPU) ran on a poor peoples’ agenda and would have taken the northern vote from the conservative Northern Peoples Congress (NPC) but for the strategy of the British colonialists who were determined to hand over the north and indeed Nigeria to a craven and loyal Ahmadu Bello. During the Second Republic Aminu Kano’s Peoples Redemption Party (PRP) powered to victory in the strategic states of Kano and Kaduna, proving that a political campaign anchored on the poor yields dividends.

If Peter Obi wants the Nigerian poor to turn out in their millions to vote for him in 2023, then he will have to give them something concrete in return. The social programmes I have spelt out in this essay, taken from the Nigerian Workers Charter Of Demands, must therefore occupy pride of place in Peter Obi’s manifesto.

Dr Okonta was until recently Leverhulme Early Career Fellow in the Department Of Politics at the University of Oxford. He now lives in Abuja

Leave a Reply